Exotic Construction Architecture History, Styles and Building Materials

- Endless Life Design

- Dec 16, 2023

- 50 min read

INDEX

"Exploring Vernacular & Inca Architecture History and their Building Materials"

"Unveiling Germanic and Moroccan Architecture: Elevation and Pediment Insights"

"Navigating Russian and Persian Architecture: Unveiling Architectural Wonders"

"In-Depth Insights into Viking and English Architecture: Architectural Columns and Services"

"Discovering Hawaiian and Jacobean Architecture: From Honolulu to Great Britan Firm"

"Revealing Turkish and Abstract Architecture: Ankara Architectural Firm"

"Engaging with Cuban and French Architecture: Interior and Elevation Drawings"

"Understanding Burmese and Gothic Architecture: A Turkmenistan Middle Ground Architectural Essence"

"Exploring Coastal and Eclectic Architecture: Europe Finest Architectural Spectrum"

"Unraveling Italian Renaissance and Greek Architecture: ELD from Milan to Greece"

"Exploring Vernacular & Inca Architecture History and their Building Materials"

Vernacular Architecture

Vernacular Architecture, stemming from the Latin word "vernaculus," meaning native or domestic, represents a rich tapestry of building styles that emerged organically within various communities and regions. Its genesis traces back to ancient civilizations where local materials, craftsmanship, and traditions fused to create functional and culturally embedded structures. This form of architecture transcends time, embodying the ethos of communities and reflecting their environmental adaptation and social customs.

The roots of Vernacular Architecture delve into the annals of history, where indigenous cultures worldwide utilized available resources ingeniously to construct dwellings suited to their climates and lifestyles. From the adobe houses of the American Southwest to the thatched-roof cottages dotting the English countryside, each structure embodies a narrative of human ingenuity intertwined with geographical influences.

Throughout history, Vernacular Architecture has evolved in response to regional needs and cultural diversity. In medieval Europe, the timber-framed houses of half-timbering construction showcased craftsmanship and adaptability. In Asia, the intricate wooden temples and courtyard houses in China and Japan epitomize harmony with nature and cultural aesthetics.

Colonial expansion and cultural exchange also influenced Vernacular Architecture, leading to amalgamations of styles and techniques. The fusion of European architectural elements with local building practices in regions like Latin America and Southeast Asia exemplifies this synergy, creating unique architectural hybrids.

Today, Vernacular Architecture continues to inspire modern design philosophies, sustainability movements, and architectural preservation efforts. Its legacy serves as a testament to the resourcefulness, creativity, and adaptability of human societies across the ages.

Vernacular Architecture Building Materials

Vernacular Architecture is characterized by its use of locally available materials and construction techniques, which varied significantly based on geographical location, climate, culture, and the resources accessible to a particular region or community. Here's an overview of common materials used during the Vernacular Architecture era across different regions:

Earth and Clay: One of the most prevalent materials worldwide was earth or clay. Adobe, rammed earth, cob, and mud bricks were extensively used for constructing walls. These materials were abundant and easily shaped into bricks or formed directly into walls. Adobe structures, made of sun-dried mud bricks, were prevalent in regions with arid climates, like parts of the American Southwest, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Wood: Timber was a primary material in many regions with forests. Various forms of timber construction, such as half-timbering in Europe or log cabins in North America, showcased the use of wood as a structural component. Wood was employed for framing, flooring, roofing, and decorative elements.

Stone: In areas with access to stone quarries, this material was extensively used for foundations, walls, and structural elements. Different forms of stone construction, from dry stone walls to intricately cut stones in monumental structures, were prevalent across regions with ample natural stone resources.

Thatch: Natural materials like straw, reeds, grasses, or palm leaves were utilized for roofing materials. Thatched roofs were common in many rural areas due to their insulating properties and availability of materials.

Bamboo: In regions where bamboo grew abundantly, it was used for construction due to its strength, flexibility, and rapid growth. Bamboo was used for framing, flooring, and sometimes even as a primary building material.

Animal Products: Animal by-products like hides, bones, and dung were occasionally used in building materials, especially in nomadic or pastoral communities.

Other Local Materials: Depending on the region, other locally available materials such as reeds, shells, volcanic rock, or even ice and snow (in colder climates) were employed in construction.

The choice of materials was influenced by factors like climate, availability, durability, and cultural preferences. Vernacular Architecture showcased ingenious methods of utilizing these materials to create structures suited to the local environment, traditions, and community needs.

Inca Architecture

Inca Architecture, an extraordinary testament to pre-Columbian engineering prowess and artistic finesse, embodies the zenith of Andean civilization. Rooted in the heart of the Andes Mountains, the Inca Empire, flourishing from the 15th to the 16th century, boasted architectural marvels that seamlessly merged with the rugged landscape. Their architectural legacy stands as a testament to sophisticated urban planning, intricate stonework, and spiritual reverence for the natural world.

The genesis of Inca Architecture can be traced to the capital city of Cusco, the epicenter of Incan culture. Here, the renowned walls of Sacsayhuamán, constructed with colossal megalithic stones meticulously fitted without mortar, epitomize the precision and ingenuity of Inca masonry techniques. This style of ashlar masonry, characterized by interlocking stones cut with remarkable precision, not only ensured structural stability but also showcased a level of craftsmanship unparalleled in the region.

Beyond the impressive city of Cusco, the crown jewel of Inca Architecture lies in the ancient citadel of Machu Picchu. Nestled amidst the mist-shrouded peaks of the Andes, this UNESCO World Heritage Site resonates with spiritual significance and architectural splendor. Machu Picchu's terraced agricultural fields, ceremonial plazas, and precisely constructed stone structures, intricately fitted together without the use of mortar, attest to the Inca's unparalleled engineering prowess and their harmonious coexistence with the environment.

The architectural prowess of the Inca extended beyond monumental structures to an extensive network of roads and bridges known as the Qhapaq Ñan. This intricate road system, stretching thousands of miles across the empire, facilitated communication, trade, and movement of people, showcasing the Inca's mastery in civil engineering.

Despite the decline of the Inca Empire due to Spanish conquest, the enduring legacy of Inca Architecture continues to captivate the world, drawing admirers and scholars alike to unravel the mysteries and brilliance embedded within the stones of their magnificent structures.

The Inca civilization's architectural legacy remains a testament to their engineering mastery, spiritual connection with nature, and adaptation to the challenging mountainous terrain.

Inca Architecture Building Materials

During the Inca Architecture Era, the Inca civilization primarily utilized locally available materials to construct their remarkable architectural feats. The Inca Empire, nestled in the Andes Mountains, exhibited an ingenious use of natural resources. The key materials employed in Inca Architecture included:

Andesite and Granite Stones: The Inca civilization is renowned for their exceptional stonework. They quarried and shaped stones, primarily andesite and granite, with precision to create massive structures. Notably, the use of ashlar masonry, where stones were cut and shaped to fit perfectly without mortar, resulted in structures like the walls of Sacsayhuamán and Machu Picchu's temples and terraces.

Adobe and Mud Bricks: In areas where stones weren't as readily available, the Inca used adobe and mud bricks. Adobe was made by mixing mud, straw, and water, then sun-drying the bricks. These materials were used for constructing houses and smaller structures.

Quartzite and Limestone: In some regions, the Inca used quartzite and limestone as building materials. These stones were often employed for less visible or structural elements, such as foundations or interior structures.

Wood and Straw: While stones were the primary building material, wood and straw were used for roofs and other secondary architectural elements. Timber was scarce at higher elevations, so the Inca used local trees sparingly, mostly for roofing purposes.

Terraced Agriculture: The Inca's terraced agricultural system, where they shaped and utilized the mountain slopes for farming, also played a significant role in their architectural landscape. These terraces required careful engineering and manipulation of the landscape.

Earth and Cob: In less monumental structures or rural areas, earth-based building techniques such as cob or rammed earth might have been used. Cob, a mixture of clay, sand, and straw, was formed into walls and allowed to dry.

The Inca Empire's architectural mastery lay in their ability to manipulate and craft these diverse materials to create structures that harmonized with their environment. Their use of locally sourced and adapted materials, coupled with innovative engineering techniques, contributed to the resilience and enduring grandeur of Inca Architecture.

Vernacular and Inca Architecture Era Vernacular Architecture doesn't have a specific inception year as it's a term that refers to indigenous or local architecture that evolves over time within various cultures and regions. It's more of an ongoing, organic process rather than an architectural movement with a defined start date. It's rooted in traditions and practices that have developed over centuries within different communities worldwide.

Inca Architecture refers to the architectural style prevalent during the Inca Empire, which reached its peak between the 15th and 16th centuries in the Andean region of South America. The Inca Empire emerged around the 15th century and flourished until the Spanish conquest in the 16th century. This period encompasses the era when the Inca civilization was at its zenith, constructing monumental structures like Machu Picchu and demonstrating their remarkable architectural prowess.

Conclusion

The exploration into Vernacular and Inca Architecture histories and their utilization of distinct building materials encapsulates a fascinating juxtaposition of cultural timelines and architectural achievements. Vernacular Architecture, evolving organically across centuries within diverse communities worldwide, lacks a specific historic date but embodies a continuum of indigenous building practices ingrained within cultures. In contrast, Inca Architecture, flourishing during the 15th and 16th centuries within the Andean region of South America, represents a more defined historic period marked by the zenith of the Inca civilization. While Vernacular Architecture spans various eras and regions, Inca Architecture shines as a testament to the remarkable engineering feats and cultural brilliance achieved within a specific historical epoch. Both styles underscore humanity's adaptability, creative resourcefulness, and profound connection with materials and the environment, albeit within different historical contexts, showcasing the enduring legacy of architectural ingenuity across time and civilizations.

"Unveiling Germanic and Moroccan Architecture: Elevation and Pediment Insights"

Germany Architecture

Germanic architecture, spanning centuries, reflects a rich tapestry of styles shaped by diverse historical, cultural, and regional influences across the Germanic-speaking regions of Europe. The roots of Germanic architectural heritage can be traced back to the early medieval period, notably the era of the Germanic tribes. During this time, structures were primarily wooden, featuring simple designs with timber-framed construction characterized by post-and-beam systems. The evolution of Germanic architecture accelerated with the spread of Christianity in the region, leading to the construction of churches and monasteries that displayed Romanesque and Gothic influences.

The Romanesque period, spanning from the 11th to the 12th centuries, saw the emergence of sturdy stone structures adorned with rounded arches, thick walls, and vaulted ceilings. Influenced by Roman and Byzantine styles, Romanesque architecture featured fortress-like churches such as the Speyer Cathedral, exhibiting a sense of grandeur and solidity. The subsequent transition to the Gothic style witnessed towering cathedrals with pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and elaborate stained glass windows. Structures like the Cologne Cathedral, a pinnacle of Gothic architecture, exemplify the intricate craftsmanship and soaring heights characteristic of this period.

The Renaissance period brought forth a shift in Germanic architecture, embracing classical elements and symmetry inspired by Italian architecture. This era saw the construction of palaces, town halls, and residences showcasing ornate facades and intricate detailing. However, the Thirty Years' War and subsequent Baroque period reshaped architectural landscapes, leading to the construction of opulent palaces and churches adorned with elaborate decoration, exemplified by the Würzburg Residence. The 19th century witnessed a revival of medieval styles like the Neo-Gothic movement, while the 20th century brought about modernist and contemporary architectural expressions that blended tradition with innovation, shaping the diverse architectural identity seen across Germanic regions today.

Germanic architecture's evolution reflects a fusion of influences, from tribal origins to the enduring legacies of Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, Baroque, and modernist movements. Its narrative unfolds through monumental structures, each era leaving an indelible mark on the architectural fabric of Europe, showcasing an amalgamation of cultural, artistic, and historical narratives that continue to shape the region's built heritage.

Germanic Architecture Building Materials

Germanic architecture, spanning various historical periods, employed a diverse range of materials reflective of the region's geographical diversity and technological advancements across different eras:

Wood: Initially, during the early Germanic period, wood was the primary building material. Timber-framed construction characterized by post-and-beam systems formed the basis of many structures. These wooden buildings featured simple designs and were prevalent due to the abundance of forests in the region.

Stone: With the advent of Romanesque and Gothic architecture, stone became a prominent building material. Churches, cathedrals, and fortresses were constructed using stone, with thick walls, rounded arches, and vaulted ceilings defining Romanesque structures, while the Gothic period emphasized pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and soaring spires in stone-built cathedrals.

Brick: The use of bricks became more prevalent during the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Brick construction adorned the facades of town halls, residences, and palaces, showcasing intricate designs and ornamentation. Notable examples include structures in northern Germany where brick Gothic architecture flourished.

Plaster and Stucco: During the Baroque period, decorative elements such as plaster and stucco played a significant role in embellishing interiors and exteriors. Elaborate stucco work adorned palaces and churches, showcasing intricate designs and ornamental features.

Metal: Iron and metalwork were also integral to Germanic architecture, especially in the construction of ornate gates, decorative elements, and hinges for doors and windows. Metalwork was used extensively in both functional and decorative aspects of buildings during different periods.

Glass: The Gothic period witnessed advancements in stained glass windows, with vibrant colored glass used to create intricate designs depicting religious narratives. These windows adorned cathedrals and churches, adding a striking visual element to the architecture.

Germanic architecture's evolution saw a transition from wood to stone, brick, and other materials, each era leaving a distinct mark on the architectural landscape of the region. The use of these materials was influenced by technological advancements, cultural preferences, and the availability of resources during different historical periods.

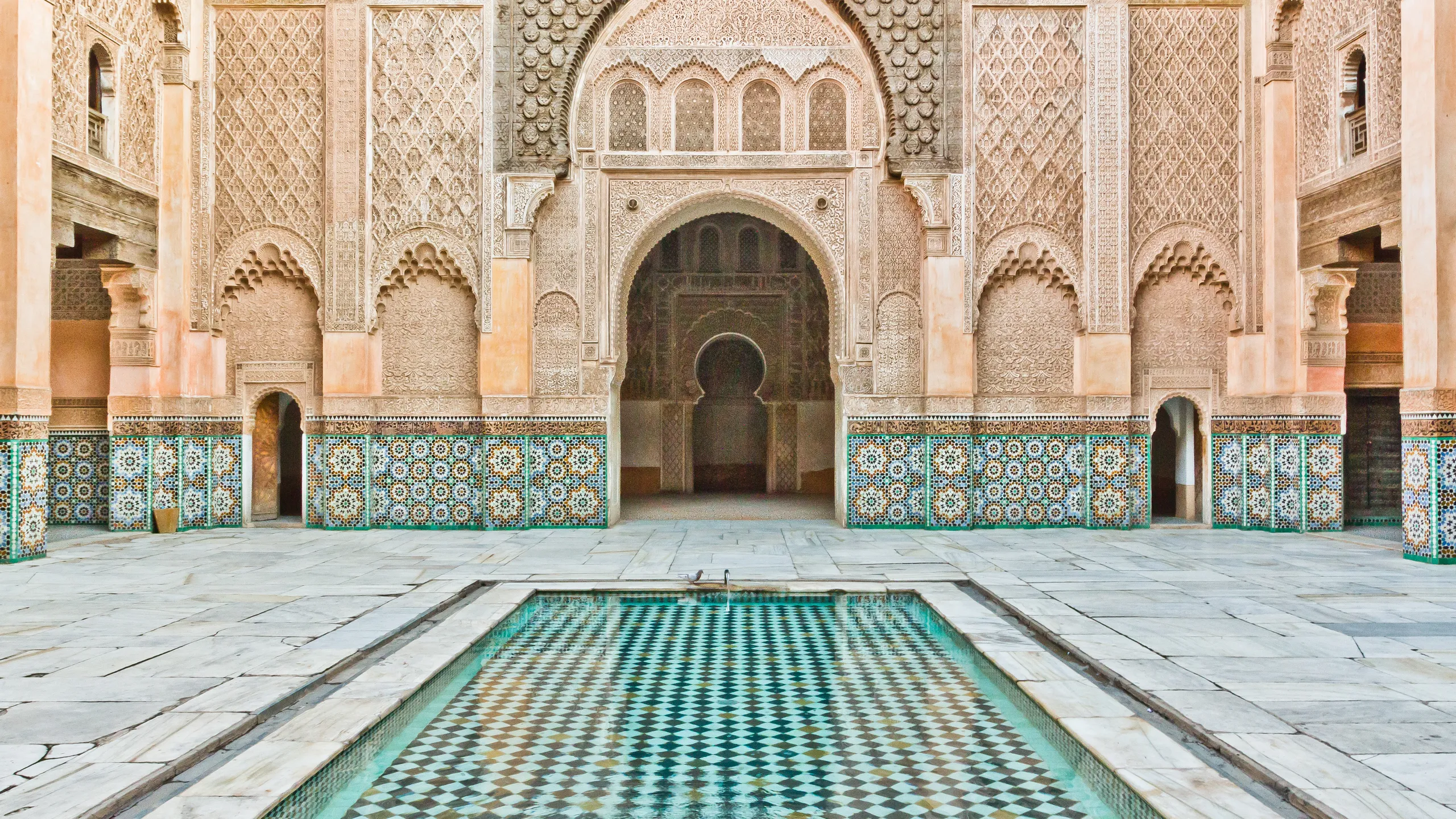

Moroccan Architecture

Moroccan architecture, a captivating blend of diverse cultural influences, bears a rich tapestry of history spanning centuries. Rooted in the amalgamation of Berber, Arab, and Andalusian traditions, Moroccan architectural styles showcase a unique synthesis of indigenous techniques and external inspirations. The earliest traces of Moroccan architecture date back to the Berber dynasties, where simple, fortified structures known as kasbahs and ksars were crafted from local materials like adobe and clay, reflecting a response to the harsh desert climate.

However, the zenith of Moroccan architecture unfolded during the Islamic period, notably during the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties. These eras witnessed the construction of iconic landmarks like the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech, characterized by intricate geometric patterns, horseshoe arches, and decorative elements that typify the region's Islamic architecture. The ornate Medersas (Islamic schools) and Riads (traditional houses with internal courtyards) emerged as architectural marvels, showcasing exquisite tilework, plaster carvings, and serene fountains that epitomize Moroccan craftsmanship.

The subsequent periods, marked by the Marinid and Saadian dynasties, witnessed a continuation and refinement of architectural styles. The Marinid era, in particular, introduced decorative elements like zellige tilework and delicate stucco carvings, adorning monuments such as the Bou Inania Madrasa in Fes. The Saadian dynasty continued this legacy with opulent palaces and gardens, exemplified by the Saadian Tombs in Marrakech, featuring intricately designed domes and exquisite marble work.

With Morocco's interaction with European powers during the colonial era, a fusion of architectural styles emerged. The French Protectorate period brought modernist influences to Moroccan architecture, seen in colonial buildings and urban planning. However, efforts to preserve and revive traditional Moroccan architecture in the post-colonial era have led to a resurgence of interest in historic techniques and designs, reinforcing the significance of Moroccan architectural heritage in contemporary times.

Moroccan architecture, an embodiment of cultural syncretism and artistic finesse, continues to stand as a testament to the country's vibrant history, reflecting the resilience, creativity, and enduring legacy of diverse civilizations that have left an indelible mark on the architectural landscape of Morocco.

Moroccan Architecture Building Materials

Moroccan architecture, known for its diverse influences and distinct styles, employed a range of materials reflective of the region's cultural heritage and climatic conditions:

Adobe and Clay: In the early periods, particularly during the Berber dynasties, adobe and clay were primary building materials. Ksars (fortified villages) and kasbahs (fortresses) were constructed using these materials due to their availability and suitability for desert climates.

Zellige and Tadelakt: Zellige, intricately designed mosaic tiles, and Tadelakt, a waterproof plaster, are hallmark materials of Moroccan architecture. Zellige tiles, crafted from colorful geometric patterns, adorned walls, floors, and domes, adding vibrant ornamentation to buildings. Tadelakt, with its polished and waterproof finish, was used in baths, hammams, and interiors.

Stone: Stone was used in various periods, especially during the Islamic dynasties like the Almoravids and Almohads, for constructing mosques, minarets, and monumental structures. Stone, often carved with intricate designs, provided durability and aesthetic appeal.

Wood: Cedar and other local woods were utilized for structural elements, such as roof beams, doors, and ornamental carvings in Moroccan architecture. Traditional Riads featured wooden ceilings and intricate woodwork in doors and windows.

Marble and Mosaic: During later periods like the Marinid and Saadian dynasties, marble and mosaic work gained prominence. Luxurious palaces and mosques showcased exquisite marble columns, fountains, and intricate mosaic patterns.

Metalwork: Moroccan architecture incorporates detailed metalwork, particularly wrought iron and brass, in decorative elements like lanterns, grilles, and door knockers. Intricate filigree designs adorned windows and doors, adding to the visual richness of buildings.

Natural Elements: Additionally, elements like water features, such as fountains and ornamental pools, were integral to Moroccan architecture, providing both functional and aesthetic value, especially in courtyards and gardens.

The use of these materials was influenced by cultural traditions, regional availability, and the climate of Morocco, resulting in the creation of distinct architectural styles that continue to shape the country's architectural landscape and cultural identity.

Germanic and Moroccan Architecture Era

Germanic architecture spans various historical periods, including the Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque eras, each leaving a distinctive mark on the architectural landscape. The Romanesque period (11th-12th centuries) witnessed projects like the Speyer Cathedral in Germany, featuring sturdy stone construction with rounded arches and thick walls. Transitioning into the Gothic era (12th-16th centuries), monumental structures like the Cologne Cathedral exemplify the era's pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and intricate stone carvings. Moving into the Renaissance and Baroque periods, Germany saw constructions like the Würzburg Residence, showcasing opulent palaces and gardens characterized by ornate facades and elaborate interior designs.

Moroccan architecture, shaped by a fusion of Berber, Arab, and Andalusian influences, experienced significant periods of architectural splendor. During the Almohad dynasty (12th-13th centuries), landmarks like the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakech highlighted the era's Islamic architectural brilliance. The Marinid period (13th-15th centuries) brought forth structures like the Bou Inania Madrasa in Fes, showcasing elaborate tilework and stucco carvings. In later periods, the Saadian dynasty's architectural projects, such as the Saadian Tombs in Marrakech, continued the tradition of exquisite domes and marble craftsmanship, shaping Morocco's architectural legacy across diverse historical epochs.

Conclusion

The comparison between Germanic and Moroccan architecture histories, coupled with their diverse building materials, unravels a captivating tale of architectural evolution and cultural distinctiveness. Germanic architecture, spanning Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque periods, employed materials like stone, wood, brick, and intricate metalwork to erect monumental structures such as cathedrals and palaces. The emphasis on sturdy stone constructions, towering cathedrals with pointed arches, and ornate facades adorned with detailed carvings exemplified the Germanic approach, reflecting spiritual and artistic aspirations through durable materials and intricate craftsmanship.

Conversely, Moroccan architecture, enriched by a blend of zellige tiles, Tadelakt plaster, adobe, clay, and intricate mosaic designs, crafted a visual symphony of geometric patterns and ornate embellishments. Moroccan architecture's distinctiveness lies in its ingenious use of materials, where the play of color, texture, and intricate mathematical detailing evokes a sense of unity, spirituality, balance, and aesthetic allure, encapsulating the essence of Islamic artistry and cultural heritage. Both architectural styles, while divergent in their approaches and materials, resonate as testimonies to the creativity and cultural identities embedded within their respective built environments, showcasing the enduring legacy of architectural brilliance across diverse civilizations.

"Navigating Russian and Persian Architecture: Unveiling Architectural Wonders"

Russia Architecture

Russian architecture has a rich and diverse history that spans many centuries, influenced by various cultural, religious, and political changes. Here are some significant construction projects from different periods in Russian architectural history:

Kremlin in Moscow (14th-17th centuries): The Moscow Kremlin is a fortified complex that includes cathedrals, palaces, and towers. The earliest structures date back to the 14th century, with subsequent additions and renovations over centuries, representing various architectural styles from medieval Russia.

St. Basil's Cathedral in Moscow (1555-1561): Known for its colorful onion domes and intricate designs, St. Basil's Cathedral was commissioned by Ivan the Terrible to commemorate the capture of Kazan and Astrakhan. It's a prime example of Russian medieval architecture.

Winter Palace in St. Petersburg (1732-1762): The former royal residence, designed by Bartolomeo Rastrelli, is a massive Baroque-style palace and a part of the Hermitage Museum complex. It showcases grandeur and opulence typical of the Baroque era.

Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow (1839-1883): A significant project of the 19th century, it was built to commemorate Russia's victory over Napoleon and was later demolished by the Soviet regime. It was reconstructed in the 1990s and stands as a symbol of revival and religious renewal.

St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg (1818-1858): Constructed under several architects, including Auguste de Montferrand, it's a stunning example of Russian neoclassical architecture. Its massive dome and grand interior make it a significant cultural and architectural landmark.

Moscow Metro Stations (1930s onwards): The Moscow Metro boasts some of the most beautiful and ornate subway stations in the world. Built in the Soviet era, these stations are known for their grand architecture, intricate designs, and artistic elements.

These construction projects showcase the evolution of Russian architecture, encompassing styles from medieval Russian architecture to Baroque, Neoclassical, and Soviet-era architectural achievements. They stand as testaments to Russia's cultural heritage and architectural prowess across different historical periods.

Russian architecture has undergone various stylistic phases throughout its history, reflecting influences from different periods and cultural interactions. Some of the main architectural styles in Russian history include:

Pre-Petrine Architecture: Before the 17th century, Russian architecture predominantly consisted of wooden structures. The early Russian churches and buildings often featured wooden construction, such as log cabins and churches made of timber.

Old Russian Architecture: This style emerged from the 11th to the 17th centuries and includes distinctive architectural elements seen in Orthodox churches and monasteries. Key features include onion domes, tent-like roofs, colorful frescoes, and intricate iconostasis (icon screens).

Moscow Baroque: This style evolved in the late 17th and early 18th centuries and is characterized by lavish ornamentation, curving shapes, and grandeur. The Moscow Baroque style can be observed in churches and palaces, notably in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Imperial Russian Architecture: During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Imperial era saw the emergence of neoclassical and empire styles influenced by Western European architecture. Architects like Rastrelli and Quarenghi designed grand palaces, government buildings, and cathedrals with symmetrical designs and classical elements.

Russian Revival Style: In the mid-19th century, there was a revival of traditional Russian architecture inspired by nationalistic sentiments. Architects sought to revive old Russian architectural forms seen in the revival of onion domes, wooden architecture, and decorative elements from earlier periods.

Soviet Architecture: After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Soviet architecture embraced constructivism and socialist realism. This period focused on functionalism, geometric shapes, and minimal ornamentation, with an emphasis on communal housing, public spaces, and industrial projects.

These styles represent the evolution of Russian architecture, each reflecting the cultural, political, and societal influences of their respective eras, contributing to the diverse and rich architectural heritage of Russia.

Russia Architecture Building Materials

Throughout Russian architectural history, various materials have been used based on the period, geographic location, and available resources. Some prominent materials include:

Wood: Traditional Russian architecture heavily utilized wood due to its abundance. Wooden structures, including log cabins, churches, and palaces, were common in early Russian architecture. Carved wooden details, such as decorative elements on houses and churches, were also prevalent.

Brick and Stone: As architecture evolved, especially during the Imperial and Soviet periods, brick and stone became widely used. Churches, palaces, government buildings, and cathedrals were constructed using stone and brick, showcasing intricate designs and ornate details.

Onion Domes: These distinctive architectural elements were made using wooden frameworks covered in metal or shingles. They were a characteristic feature of Russian Orthodox churches, giving them their iconic appearance.

Stucco, Plaster, and Paint: Decorative elements in Russian architecture often included stucco, plaster, and vibrant paint colors. Elaborate frescoes, ornamental details, and religious icons adorned many structures, particularly Orthodox churches.

Metal: Metal, including wrought iron and cast iron, was used for decorative elements such as railings, gates, and decorative features on buildings, especially during the Imperial era.

Concrete and Steel: In the Soviet era and modern times, materials like concrete and steel became more prevalent, especially in the construction of large-scale buildings, industrial projects, and housing complexes.

The diverse architectural styles across Russian history have led to a varied use of materials, from natural elements like wood to more industrial materials like concrete and steel. The choice of materials often reflects the technological advancements, cultural influences, and regional characteristics prevalent during different periods of Russian architectural development.

Persian Architecture

Persian architecture has a rich history that spans several millennia, characterized by its diverse influences, intricate designs, and innovative engineering. The architectural legacy of Persia, now modern-day Iran, reflects various cultural, religious, and historical periods:

Ancient Persian Architecture (c. 550 BC - 651 AD): The Achaemenid Empire, notably under Cyrus the Great and Darius I, created monumental structures like Persepolis and Pasargadae. These sites showcased grand palaces, massive columns, and intricate relief carvings on stone.

Sassanian Architecture (224-651 AD): The Sassanian dynasty contributed to Persian architecture with distinctive features like the domed roofs, arches, and elaborate palace structures. Notable examples include the Taq Kasra (the Arch of Ctesiphon) and the palace at Firuzabad.

Islamic Period (7th century onwards): With the advent of Islam, Persian architecture experienced new influences. Islamic architectural features like domes, minarets, intricate tilework (mosaics), and geometric patterns became prominent. The Jameh Mosque of Isfahan and the Imam Mosque in Isfahan exemplify this era's architectural grandeur.

Seljuk and Mongol Periods (11th-13th centuries): During this period, Persian architecture continued to evolve. The Seljuk architecture, seen in structures like the Jameh Mosque of Nain and the Friday Mosque of Isfahan, showcased unique innovations in design and ornamentation.

Safavid Dynasty (16th-18th centuries): The Safavid era witnessed the construction of iconic landmarks such as the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque and the Shah Mosque in Isfahan. These structures displayed the exquisite use of tilework, vibrant colors, and grand-scale designs.

Qajar and Modern Period (18th century onwards): The Qajar era brought about a blend of Persian, European, and Russian influences. Palaces, bridges, and public buildings with distinct Persian elements emerged during this period.

Throughout its history, Persian architecture has been characterized by its use of geometric patterns, intricate tilework, decorative calligraphy, innovative use of space, and a harmonious blend of form and function. The legacy of Persian architecture continues to influence contemporary design, preserving its cultural significance and architectural excellence.

Persian Architecture Building Materials

Persian architecture, across its diverse historical periods, has employed various building materials based on the technological advancements, regional availability, and cultural preferences. Some of the primary materials used in Persian architecture include:

Brick: Persian architecture extensively used fired and glazed bricks. These bricks were often decorated with intricate geometric patterns, calligraphy, and colorful tilework. The use of brick was prevalent in constructing walls, domes, and intricate architectural details.

Stone: Natural stone, including limestone, marble, and sandstone, was commonly used in monumental structures, palaces, mosques, and tombs. Notable examples include the use of marble in intricate carvings and decorative elements.

Mud Brick (Adobe): Especially in ancient Persian architecture, mud brick or adobe was a prevalent building material due to its availability and ease of construction. Structures like ancient ziggurats and dwellings often used adobe bricks.

Wood: Timber, though not as commonly used in monumental structures, was employed in the construction of roofs, ceilings, and decorative elements in palaces, houses, and traditional structures.

Tilework and Ceramics: Persian architecture is renowned for its exquisite tilework, intricate mosaics, and decorative ceramics. Vibrant colored tiles, often featuring intricate geometric patterns, floral motifs, and calligraphy, adorned the exteriors and interiors of buildings.

Plaster and Stucco: These materials were used for finishing touches on walls, ceilings, and architectural elements. They provided a smooth surface for intricate decorative motifs, calligraphy, and relief carvings.

Metal: Metals like bronze, copper, and brass were utilized for decorative purposes, including ornate doors, gates, and details on religious buildings.

The ingenious use of these materials, combined with skilled craftsmanship, led to the creation of some of the most iconic and visually striking architectural masterpieces in Persian history. The intricate details, colorful ornamentation, and meticulous craftsmanship using these materials remain a hallmark of Persian architectural design.

Conclusion

Both Russian and Persian architecture boast rich and diverse histories marked by unique styles and innovative building materials. While Russian architecture exhibits a blend of wood, brick, stone, and ornate decorative elements like onion domes and frescoes, Persian architecture stands out for its intricate tilework, vibrant ceramics, and the skilled use of fired bricks, stone, and decorative calligraphy. The two cultures utilized regional materials innovatively—Russia favored sturdy stone and brick for monumental structures, emphasizing grandeur and ornate detailing, while Persia's mastery lay in intricate tilework and the artful use of vibrant colors and patterns, creating visually striking architectural marvels. Both legacies, though distinct, reflect a deep cultural heritage and a commitment to architectural excellence through ingenious use of available building materials.

"In-Depth Insights into Viking and English Architecture: Architectural Columns and Services"

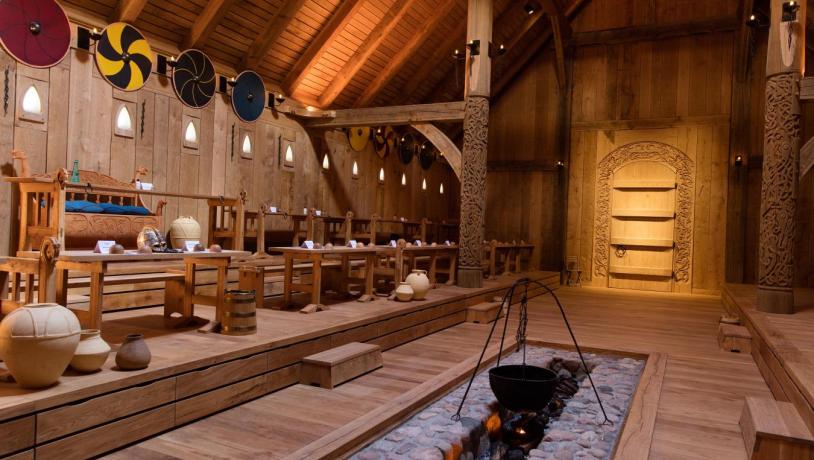

Viking Architecture

Viking architecture, associated with the Norse people from the late 8th to the 11th centuries, was primarily characterized by sturdy, practical structures that included homes, halls, and religious buildings. Notable constructions and dates within Viking architectural history include:

Viking Longhouses (8th-11th centuries): These were the primary dwelling structures of the Vikings. Longhouses were elongated wooden structures with thatched roofs, stone or turf walls, and a central hearth. Examples have been found across Scandinavia, showcasing the practical and communal nature of Viking domestic architecture.

Trelleborg Fortresses (10th century): These ring-shaped fortresses, such as Trelleborg in Denmark, were strategic military structures characterized by circular layouts, earthworks, and precise construction. The purpose of these fortresses was to control territories and defend against potential enemies.

Borre Mounds (9th century): The Borre mounds in Norway represent burial sites for Viking elites. These monumental burial mounds, some over 20 meters in diameter, indicate the importance and social hierarchy within Viking society.

Urnes Stave Church (12th century): Though slightly later than the Viking era, the Urnes Stave Church in Norway is an example of early Scandinavian Christian architecture with influences from Viking design. It showcases intricate wood carvings and distinctive ornamentation.

Viking architecture emphasized functionality, using locally available materials like wood, stone, and turf for construction. Their structures often exhibited practicality, adaptability to harsh environments, and reflected the societal norms and beliefs of the Viking Age. These constructions offer valuable insights into the architectural and cultural aspects of Viking society.

Viking Architecture Building Materials

During the Viking architectural era, which spanned roughly from the late 8th to the 11th centuries, the Norse people primarily utilized locally available natural materials to construct their buildings. Some of the key building materials used during the Viking Age included:

Wood: Wood was the most prevalent material for Viking construction due to its abundance in the Scandinavian region. Oak, pine, and other types of timber were used to build longhouses, ships, and various structures. Longhouses, the primary dwelling of the Vikings, were constructed using wooden frames, walls, and thatched roofs.

Stone: While less common than wood, stone was also utilized in Viking architecture. It was used for foundations, support structures, and occasionally for walls, especially in more permanent structures like fortresses or religious buildings. Stones were typically sourced locally and used in conjunction with wood for structural integrity.

Turf: In some areas with limited timber resources, Vikings used turf or sod to insulate and reinforce their buildings. Turf walls were often used in conjunction with timber frames and stones to construct dwellings, providing additional insulation against harsh weather conditions.

Thatch: Thatched roofs made of straw, reeds, or grasses were commonly used to cover the wooden frames of Viking buildings, including longhouses and smaller dwellings. Thatch provided protection from rain and helped insulate the interiors.

Clay and Mud: These materials were sometimes used for daubing or plastering walls, filling gaps between wooden beams, or reinforcing construction in some structures. They were often mixed with straw or other organic materials to enhance their binding properties.

The Viking architectural style was characterized by its resourcefulness and adaptability to the natural environment. The use of locally sourced materials such as wood, stone, turf, thatch, and simple construction techniques were essential in creating functional and durable structures suited to the Viking way of life.

English Architecture

English architecture spans a vast historical timeline, showcasing various styles and influences from different periods. Some significant construction projects and their dates in English architectural history include:

Roman Architecture (43-410 AD): The Romans introduced architectural styles to England during their occupation. Notable constructions include the Roman city walls, baths, and villas such as Fishbourne Roman Palace, showcasing elements like arches, columns, and mosaics.

Norman Architecture (11th-12th centuries): After the Norman Conquest in 1066, Norman architecture flourished. The construction of Durham Cathedral (1093-1133) and the Tower of London (1078-1097) exemplifies Norman Romanesque architecture with massive stone walls, rounded arches, and thick columns.

Gothic Architecture (12th-16th centuries): The Gothic era saw the development of iconic cathedrals and churches across England. Canterbury Cathedral (1070-1834) and Westminster Abbey (1245-1517) exemplify Early English and Perpendicular Gothic styles, featuring pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and elaborate stained glass windows.

Tudor Architecture (15th-16th centuries): Tudor buildings, such as Hampton Court Palace (1515-1690), exhibit distinctive half-timbered structures with exposed wooden frames filled with plaster or brick. These buildings often feature ornate chimneys and decorative elements.

Georgian Architecture (18th century): Georgian architecture introduced symmetry and classical elements. The Royal Crescent in Bath (1767-1775) and the neoclassical style of buildings like the Bank of England reflect this period's grandeur, characterized by columns, symmetry, and refined ornamentation.

Victorian Architecture (19th century): The Victorian era saw a diverse range of architectural styles, from Gothic Revival (e.g., Houses of Parliament, 1837-1860) to Italianate and Queen Anne styles. The Crystal Palace (1851) showcased the use of iron and glass in grand exhibition spaces.

Modern and Contemporary Architecture (20th-21st centuries): Notable structures include the Art Deco-style Battersea Power Station (1933) and the postmodernist Lloyd's Building (1986) in London, showcasing innovative designs and materials.

These constructions represent England's architectural evolution, showcasing diverse styles, technological advancements, and cultural influences across different historical periods.

English Architecture Building Materials

Throughout English architectural history, various building materials have been utilized to construct iconic structures reflective of their respective eras. Some of the prominent building materials used in different periods of English architecture include:

Stone: Stone was a primary material in many eras, from Roman times through the medieval period and into the Georgian era. Limestone, sandstone, and granite were commonly used for constructing cathedrals, castles, and grand buildings due to their durability and aesthetic appeal.

Timber: Timber was a fundamental material in early English architecture and the Tudor period. Half-timbered houses with exposed wooden frames filled with wattle and daub (a mixture of mud, straw, and clay) characterized the Tudor architectural style.

Brick: Brick gained prominence during the Tudor era and became more prevalent in subsequent periods, especially during the Georgian and Victorian eras. Buildings, such as Georgian townhouses and Victorian terraces, utilized bricks due to their versatility and ease of mass production.

Iron and Steel: The Industrial Revolution brought about the use of iron and later steel in construction. Cast iron was utilized for bridges, structures, and ornamental elements, while steel became integral in constructing skyscrapers and modern buildings.

Glass: The development of larger glass panes in the Victorian era facilitated the use of glass in windows, conservatories, and ornate structures. The Crystal Palace, an iconic Victorian structure, showcased the use of glass and iron on a grand scale.

Concrete: Concrete gained popularity in the 20th century and became a prevalent building material for various structures due to its versatility, strength, and cost-effectiveness.

These materials, along with others like lead, copper, and various decorative elements, were used innovatively across different periods in English architecture, contributing to the diverse and rich architectural heritage of England.

Viking And English History Architectural Columns and Services

Both Viking and English architectures utilized architectural columns, although they were used differently in each style:

Viking Architectural Columns: Viking architecture predominantly employed timber-based construction for their buildings. While the use of architectural columns wasn't as prevalent or ornate as in classical architecture, columns or supports were occasionally used to provide structural support in certain Viking structures. In buildings like longhouses or halls, wooden columns or posts were used to support the roof structure, creating an open interior space. These columns were usually simple and functional, serving as load-bearing elements rather than decorative features.

English Architectural Columns: In contrast, columns played a significant role in various periods of English architecture, especially during eras influenced by classical styles such as Romanesque, Gothic, and Classical Revival. Columns were prominent features in cathedrals, churches, palaces, and other grand buildings. They were often elaborately decorated with intricate carvings, capitals, and moldings, serving both structural and decorative purposes. Columns in English architecture varied in style, including round columns (dorics, ionics, and corinthians), clustered columns, and engaged columns integrated into walls.

While both architectural styles incorporated columns to some extent, the use and significance of columns differed significantly between Viking and English architectures due to their respective cultural, historical, and design influences.

In terms of providing construction services in a modern context, neither Viking nor early English architecture aligns with the conventional understanding of offering professional architectural or construction services as we know them today:

Viking Architecture Services: Viking architectural practices were largely communal and based on local craftsmanship within the community. They relied on traditional knowledge passed down through generations rather than formalized professional services. While skilled individuals within the Viking society might have led construction projects, there wasn’t a professionalized system akin to modern architecture firms or construction services.

Early English Architecture Services: Similarly, during early English architectural periods, particularly in the medieval and early modern eras, the construction industry operated differently from contemporary practices. Building projects were often overseen by master craftsmen, masons, and artisans. Guilds, comprised of skilled craftsmen, existed, but they were focused on specific trades (like stonemasonry or carpentry) rather than offering comprehensive architectural or construction services as we conceive them today.

In essence, neither Viking nor early English architecture directly aligned with offering professional architectural or comprehensive construction services in the way modern architecture and construction firms operate. The construction and design processes during these historical periods were community-based or led by skilled artisans rather than formalized professional services we recognize in contemporary times.

Conclusion

Endless Life Design Construction Company adeptly navigates the unique building materials and techniques intrinsic to Viking and English architectural legacies. In Viking architecture, the utilization of timber, stone, and thatch defined the era's structural resilience and pragmatic design. Embracing these elements, our company infuses projects with the enduring strength of timber, the rustic charm of stone, and the warmth of thatched roofing, echoing the Viking penchant for sturdy constructions seamlessly melded with nature.

On the other hand, English architecture, marked by its diverse periods, celebrates the versatility of stone, brick, and timber across its historical tapestry. Leveraging these materials, our company harnesses the solidity of stone, the intricate allure of brickwork, and the timeless elegance of timber beams. By encapsulating the essence of English architectural heritage, Endless Life Design Construction Company crafts spaces that harmoniously blend historic charm with contemporary functionality, embodying the resilience and grace inherent in both Viking and English architectural traditions.

"Discovering Hawaiian and Jacobean Architecture: From Honolulu to Great Britain Firm" | Exotic Construction History, Styles and Building Materials

Hawaiian Architecture

Hawaiian architecture has a rich cultural heritage that reflects the indigenous knowledge, resources, and traditions of the Hawaiian Islands. Key architectural styles and constructions in Hawaiian history include:

Heiau Temples (Pre-contact Period): Heiaus were sacred places of worship and ritual. These temples varied in size and purpose, from simple shrines to large, elaborate platforms. Pu'ukoholā Heiau (1790) and Hale o Keawe at the Pu'uhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park are notable examples.

Hale (Dwellings): Traditional Hawaiian houses or hale were constructed with natural materials like wood, thatch, and pili grass. They typically had a rectangular shape with a high-pitched roof and open sides to allow airflow. Hale Kealoha in Lahaina, reconstructed according to traditional methods, showcases this style.

Puuhonua (Places of Refuge): These were sacred sites where individuals seeking safety from persecution or violating kapu (sacred laws) could find sanctuary. Pu'uhonua o Hōnaunau on the Big Island is an important historical site exemplifying this concept.

Ali'i Palaces and Royal Residences: Palaces and residences of Hawaiian royalty were significant architectural projects. Iolani Palace in Honolulu (completed in 1882) served as the official residence of the Hawaiian monarchs and is a symbol of Hawaiian sovereignty.

Missionary and Western Influence: Following Western contact, architectural styles in Hawaii evolved with influences from European and American traditions. Notable structures like the Kawaiaha'o Church (1842) and the Cathedral of Saint Andrew (1867) reflect this influence.

Hawaiian architecture is deeply rooted in the culture, beliefs, and natural environment of the islands. Traditional constructions prioritized sustainability, harmony with nature, and adherence to spiritual and cultural practices. Over time, external influences have shaped and transformed Hawaiian architectural styles, resulting in a diverse range of structures that reflect the islands' historical and cultural evolution.

Hawaiian Architecture Building Materials

Traditional Hawaiian architecture incorporated natural materials found abundantly across the islands. Some of the key building materials used in Hawaiian architecture history include:

Wood: Indigenous woods like koa, ʻōhiʻa, and kukui were utilized for structural elements such as posts, beams, and framing in the construction of traditional hale (houses), heiau (temples), and other buildings. These woods were prized for their durability and strength.

Thatch and Grasses: Thatched roofs were common in traditional hale, made from pili grass or lauhala leaves (from the pandanus tree). The thatch provided protection from rain and helped regulate interior temperatures.

Volcanic Rock: Basaltic lava rock, readily available in the Hawaiian Islands due to volcanic activity, was used for constructing walls, platforms, and the foundations of heiau. Stones were often meticulously fitted together without mortar.

Coral and Limestone: In some coastal areas, coral and limestone were used in construction. Coral was employed in creating walls, especially for fishponds or in heiau construction near the ocean.

Plant Fibers: Fiber from various plants, including coconut husks and olonā (a type of native nettle), was used for cordage, lashings, and bindings, securing structural components together.

Soil and Earth: In certain construction techniques, like the building of low walls or boundaries, soil and earth were utilized, often compacted to create stable structures.

Hawaiian architecture ingeniously utilized materials sourced from the islands' natural environment. The selection of these materials reflected the indigenous people's deep understanding of their surroundings and their commitment to sustainable building practices, creating structures that harmonized with the island's landscape and climate.

Jacobean Architecture

Jacobean architecture emerged during the reign of King James I of England, from roughly 1603 to 1625. This architectural style reflected the transitional phase between the Elizabethan and later Renaissance architectural styles. Key features of Jacobean architecture included symmetrical facades, elaborate decorations, and a mix of Renaissance and Gothic elements. Notable constructions from the Jacobean era include:

Hatfield House (1607-1611): Built by Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, this grand country house in Hertfordshire is a classic example of Jacobean architecture. It features symmetrical facades, mullioned windows, and Dutch-style gables.

Hampton Court Palace (1514-1690): Originally built by Cardinal Wolsey, later expanded by King Henry VIII, and used extensively by King James I, Hampton Court Palace showcases both Tudor and Jacobean architectural elements. The Great Hall and the Clock Court are notable examples of Jacobean design.

The Queen's House, Greenwich (1616-1635): Designed by Inigo Jones, this building is regarded as one of the first examples of classical Palladian architecture in England. While it marked a departure from Jacobean style, it embodies the transition towards classical forms.

Bolsover Castle (1612-1621): Bolsover Castle in Derbyshire exemplifies the transition from medieval to Jacobean architecture. It features decorative elements typical of the Jacobean era, such as ornate chimneys and decorative stonework.

Jacobean architecture was characterized by its ornate detailing, use of classical motifs, and a move towards more symmetrical and structured designs. It marked a period of transition and experimentation, blending elements from earlier Tudor styles with emerging Renaissance influences. The architectural legacy of the Jacobean era contributed to the evolution of English architectural styles during the early 17th century.

Jacobean Architecture Building Materials

During the Jacobean architectural era in England (roughly 1603-1625), a variety of building materials were employed to construct structures showcasing the distinctive features of this transitional architectural style. Some of the key building materials used during the Jacobean era included:

Timber: Jacobean buildings often utilized timber framing, sometimes with elaborate decorative details. Oak was commonly used due to its strength and durability. Half-timbered houses were a prominent feature during this period.

Brick: Brick became increasingly popular as a building material, especially for the construction of chimneys and decorative elements. Brickwork was employed in both structural and decorative aspects of buildings.

Stone: Stone, particularly limestone and sandstone, was used in construction, often for foundations, window surrounds, and ornamental features. Ashlar stone (finely cut and squared) was employed for more decorative aspects of facades.

Plaster and Stucco: Plaster and stucco were used for wall finishes and decorative moldings. Ornate plasterwork adorned interiors, including ceilings and walls, showcasing intricate designs.

Lead and Glass: Lead was used for the flashing and joints in roofing, while glass became increasingly available in larger panes, allowing for more expansive windows and decorative glazing.

Roofing Materials: Thatched roofs were still prevalent in rural areas, while in more urban settings, tiled or slated roofs became common.

The Jacobean era witnessed a blend of traditional building materials, such as timber and stone, with emerging materials like brick and ornamental plasterwork. The use of these materials helped create the distinctive features and ornate detailing seen in Jacobean architecture, marking a transition from earlier medieval styles towards more structured and decorative designs.

From Los Honolulu to Great Britan Firm

Endless Life Design Construction Company, spanning from Honolulu to Great Britan, stands as a beacon of innovative construction services, drawing inspiration from two distinct historical architectural periods: the Hawaiian Architecture History Era and the Jacobean Architecture History Era. Embracing the spirit of Hawaiian architecture, our company adeptly implements time-honored construction techniques that were intrinsic to the islands' heritage. These techniques include the skillful use of natural materials such as volcanic rock, indigenous woods like koa and ʻōhiʻa, and thatching methods with pili grass or lauhala leaves. Much like the Hawaiians, our construction ethos prioritizes sustainable and environmentally conscious approaches, harmonizing with the landscape and traditions while ensuring structural integrity.

Simultaneously, Endless Life Design Construction Company pays homage to the elegance of the Jacobean era. Our expertise encompasses the intricate techniques characteristic of Jacobean architecture, utilizing materials like timber framing, ornate plasterwork, brick, and stone. We embrace the structured yet decorative designs prevalent in this era, incorporating elaborate timber detailing, brick facades, and stone embellishments into our projects. The meticulous craftsmanship of this period inspires our approach, infusing sophistication and timeless elegance into every structure we build, echoing the grandeur and refinement of Jacobean design sensibilities.

By synergizing the wisdom of the Hawaiian Architecture History Era's sustainable practices with the sophisticated craftsmanship of the Jacobean Architecture History Era, Endless Life Design Construction Company endeavors to craft spaces that seamlessly blend tradition, innovation, and enduring beauty.

To book your next New Construction Engineering Architecture Project feel free to schedule your New Initial Engineering Consultation Site Visit with us.

Conclusion

The architectural histories of Hawaiian and Jacobean eras unfold with distinct narratives reflected in their choice of building materials. Hawaiian Architecture, steeped in the island's natural resources, celebrated volcanic rock, indigenous woods like koa and ʻōhiʻa, thatch, and plant fibers, resonating with sustainability and a deep reverence for the environment. In contrast, Jacobean Architecture, a product of transitional styles, embraced a blend of timber, brick, stone, plaster, and lead, showcasing a fusion of durability, ornate detailing, and emerging sophistication. The juxtaposition of these histories illuminates the dichotomy between resource-conscious, nature-integrated designs of Hawaiian heritage and the structured, decorative elegance seen in Jacobean constructions. These contrasting approaches to materials underscore diverse cultural influences, offering a rich tapestry of architectural legacies that continue to inspire modern construction practices and philosophies worldwide.

With a footprint spanning from Honolulu to Great Britain and extending worldwide, our dedication to weaving these historical architectural legacies into modern construction approaches defines our commitment to creating spaces that honor tradition while embracing contemporary functionality and beauty. This unique synthesis embodies our pursuit of crafting architectural masterpieces that endure, harmonizing the ethos of two distinct historical eras into the fabric of today's architectural landscape.

"Revealing Turkish and Abstract Architecture: Ankara Architectural Firm"

Turkish Architecture

Turkish architecture boasts a rich history that spans various periods, each contributing distinct styles and monumental structures.

Byzantine Era (330-1453): Istanbul, formerly Constantinople, was the heart of Byzantine architecture. The Hagia Sophia, originally built in 537, is a stunning example of Byzantine architecture transformed into a mosque during the Ottoman period. Its massive dome, intricate mosaics, and innovative architectural features make it an iconic structure.

Ottoman Era (1299-1922): The Ottoman Empire's architectural prowess is exemplified in structures like the Topkapi Palace (completed in the 15th century), renowned for its opulence and expansive courtyards. The Blue Mosque (Sultan Ahmed Mosque), constructed between 1609 and 1616, stands as a remarkable achievement in mosque design with its stunning blue tiles and multiple domes.

Seljuk Era (1037-1194): Notable constructions include the Alaeddin Mosque in Konya (built in the 12th century), showcasing Seljuk architectural characteristics like intricate geometric patterns and ornate details.

Each period contributes unique architectural marvels, blending elements of Islamic, Byzantine, and local influences, showcasing Turkey's diverse cultural heritage and architectural ingenuity.

Turkish Architecture Building Materials

Throughout Turkish architectural history, various building materials were utilized, reflecting the diverse cultural influences and construction techniques prevalent during different eras:

Stone: Stone was a fundamental material in Turkish architecture. Limestone and marble, sourced abundantly in Turkey, were prominently used for walls, columns, and intricate carvings. Notable structures like the Hagia Sophia and various mosques showcase elaborate stonework.

Brick: Bricks were extensively employed, especially in vaults, domes, and smaller structures. They were often used in conjunction with other materials like stone or mortar.

Tile and Ceramics: Decorative tiles and ceramics, known as "Iznik tiles" due to their production in the town of Iznik, adorned many Turkish buildings. These tiles featured vibrant colors and intricate patterns, enhancing the aesthetic appeal of structures like mosques and palaces.

Wood: Turkish architecture often incorporated wood in various elements such as doors, windows, ceilings, and interior decorations. Timber was prevalent in structures like wooden houses and palace interiors.

Plaster: Plaster was used for interior wall finishes, and ornamental details, often featuring intricate carvings and decorative motifs.

Metal: Metals like bronze, copper, and iron were employed for decorative elements, such as door handles, railings, and ornamental work.

The utilization of these materials showcased the ingenuity and craftsmanship of Turkish architects and artisans across different periods, contributing to the unique and diverse architectural heritage of Turkey.

Abstract Architecture

Abstract architecture, often associated with modern and contemporary movements, is characterized by innovative, non-conventional designs that depart from traditional architectural norms. It's a diverse field where artistic expression and experimental forms take precedence over adherence to specific historical styles. While there might not be specific historical projects solely categorized as "abstract architecture," certain influential buildings and movements exemplify abstract architectural principles:

Deconstructivism (Late 20th Century): Architects like Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid are associated with deconstructivist principles, characterized by fragmented forms, unconventional shapes, and a sense of disorientation. Gehry's Guggenheim Museum Bilbao (completed in 1997) and Hadid's Vitra Fire Station (built in 1993) exemplify this style.

Futurism (Early 20th Century): The Futurist movement, primarily in Italy, embraced abstract concepts in architecture. Although few Futurist buildings were realized, the Casa del Fascio in Como, designed by Giuseppe Terragni (completed in 1936), embodied some Futurist elements with its geometric shapes and functionalist design.

Minimalism and Contemporary Abstract Architecture: Buildings like the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing by Rem Koolhaas's firm OMA (completed in 2012) or the Burj Khalifa in Dubai (completed in 2010) demonstrate abstract qualities in their sleek, minimalist designs and innovative structural approaches.

Abstract architecture, as a concept, transcends specific dates or projects. It's an ongoing exploration of pushing boundaries, experimenting with forms, materials, and spatial experiences, often aiming to provoke emotions and challenge conventional perceptions of space and design.

Abstract Architecture Building Materials

Abstract architecture's diverse nature often involves experimentation with various materials to achieve unconventional designs and structures. The materials used in abstract architecture vary widely based on the specific project, architect, and era. However, some common materials prevalent in abstract architecture include:

Steel and Glass: Abstract architecture often incorporates steel frames and glass panels to create sleek, modern, and transparent facades. These materials allow for innovative shapes and structural designs while providing transparency and a sense of openness.

Concrete: Reinforced concrete is frequently used in abstract architecture for its flexibility in shaping unique forms and its structural strength. Architects can mold and shape concrete into unconventional geometries, contributing to abstract design elements.

Aluminum and Composite Materials: Lightweight and versatile materials like aluminum and composite panels are utilized in abstract architecture for their adaptability in creating dynamic facades and intricate designs.

Polymers and Plastics: Modern abstract architecture occasionally involves the use of polymers and high-tech plastics for their flexibility in creating unconventional shapes, translucent properties, and lightweight characteristics.

Natural Stone and Wood: While less common, abstract designs sometimes integrate natural elements like stone or wood in unique ways, juxtaposing them with more modern materials to create striking contrasts.

The materials used in abstract architecture aim to challenge traditional perceptions and push the boundaries of what is architecturally achievable. Architects often combine different materials to create structures that embody innovation, experimentation, and a departure from conventional building methods.

Ankara Architectural Firm

Endless Life Design Construction Company stands as a global beacon of architectural innovation, harnessing the essence of two distinct historical eras—the Turkish Architecture History Era and the Abstract Architecture History Era—to craft unparalleled construction services that transcend boundaries. With a meticulous approach reminiscent of Turkish architectural finesse, our company seamlessly integrates ancient techniques of stone masonry, exquisite tile work, and elaborate geometric designs into contemporary projects. Embracing the heritage of Turkish architecture, we infuse spaces with the rich tapestry of Ottoman and Byzantine influences, ensuring a harmonious blend of tradition and modernity.

Simultaneously, our endeavors encompass the avant-garde spirit of abstract architecture, where form and function converge in groundbreaking designs. By embracing unconventional materials and innovative structural concepts reminiscent of the Abstract Architecture History Era, we sculpt spaces that defy norms, echoing the ethos of deconstructivism and futurism. Our global footprint, spanning from Turkey, Ankara to every corner of the world, bears witness to our commitment to pushing architectural boundaries. From sleek steel and glass compositions to experimental forms using concrete and polymers, our constructions epitomize the abstract, inviting awe and inspiration across continents.

Endless Life Design Construction Company's dedication to merging the timeless techniques of Turkish architecture with the avant-garde concepts of abstract architecture redefines the modern architectural landscape, creating spaces that transcend time, geography, and conventional norms, leaving an indelible mark on the world of construction.

Conclusion

The architectural narratives of Turkish and Abstract history converge on their distinct material choices. Turkish architecture, steeped in tradition, celebrates locally sourced stone, intricate tiles, and ornate wood, showcasing a reverence for craftsmanship and heritage. In contrast, Abstract architecture transcends conventions, employing modern marvels like steel, glass, and polymers, pushing boundaries with unconventional forms and innovative material compositions. This dichotomy between tradition-bound materials of Turkish heritage and the avant-garde materials in Abstract architecture underscores a spectrum of cultural influences, symbolizing a blend of historical reverence and groundbreaking innovation within the architectural realm.

Endless Life Design Construction Company excels in seamlessly integrating Turkish and Abstract construction styles finest techniques in Turkey, Ankara. For residential customers seeking a touch of spirit, heritage and tradition, our mastery of Turkish architecture brings forth exquisite craftsmanship, using indigenous materials and intricate designs to infuse homes with cultural richness.

Simultaneously, for those inclined towards modernity and innovation, our expertise in Abstract architecture offers avant-garde designs, incorporating cutting-edge techniques and unconventional materials to sculpt spaces that embody sophistication and visionary aesthetics.

Our versatile approach caters to diverse tastes, ensuring personalized experiences for every residential project. Whether it's creating a home that echoes the warmth and timelessness of Turkish heritage or crafting a contemporary space that redefines architectural norms, Endless Life Design Construction Company benefits homeowners seeking bespoke, high-quality constructions that harmonize tradition with innovation. Our commitment lies in delivering tailored, exceptional historic spaces that elevate lifestyles and reflect the unique preferences and aspirations of each client.

Engaging with Cuban and French Architecture: Interior and Elevation Drawings

Cuban Architecture

Cuban architecture showcases a diverse blend of influences spanning several centuries:

Spanish Colonial Era (16th to 19th centuries): The influence of Spanish colonial architecture is evident in Havana's historic district, particularly in structures like the Castillo de la Real Fuerza (completed in 1577), the Cathedral of Havana (constructed in the 18th century), and the San Carlos de la Cabaña Fortress (built in the late 18th century).

Neoclassical and Art Deco Period (early 20th century): Havana saw a surge in architectural styles during the early 20th century, featuring Neoclassical and Art Deco influences. The Capitolio Nacional (completed in 1929), resembling the U.S. Capitol, stands as a prime example of Neoclassical architecture, while the Bacardi Building (erected in the 1930s) reflects stunning Art Deco design.

Modernist Movement (mid-20th century): The National Schools of Art (inaugurated in the 1960s) in Havana, designed by Ricardo Porro, Vittorio Garatti, and Roberto Gottardi, exemplify the modernist movement's experimental and sculptural approach to architecture.

Cuban architecture's evolution showcases a fusion of colonial, neoclassical, art deco, and modernist influences, reflecting the island's rich cultural heritage and historical transformations.

Cuban Architecture Building Materials

Throughout Cuban architectural history, several materials have been used, reflecting the diverse influences and styles prevalent during different periods:

Masonry and Stone: Particularly evident in colonial structures, masonry and stone were primary building materials. These materials were employed in fortresses, churches, and government buildings, showcasing durability and strength.

Wood: Wood was used in various elements of Cuban architecture, including doors, windows, and interior finishes. Traditional wooden balconies and shutters are prominent features in colonial-era buildings.

Tiles: Decorative tiles, often with vibrant colors and intricate patterns, were used in flooring, walls, and facades, especially in buildings influenced by Spanish colonial and Moorish architecture.

Concrete and Reinforced Concrete: Modernist and mid-20th-century constructions utilized concrete extensively, showcasing functionalist design principles and offering flexibility in shaping innovative forms.

Steel and Glass: The emergence of modern architectural styles, such as Art Deco and mid-century modern, saw the incorporation of steel frames and glass panels for sleek and futuristic designs.

Brick: Bricks were commonly used in various periods, especially in construction techniques like the colonial "techos de viga y losa" (beam and slab roofs) and in more contemporary buildings.

The use of these materials across different eras in Cuban architecture reflects a blending of traditional, colonial, and modern influences, contributing to the island's rich architectural tapestry.

French Architecture

French architecture boasts a rich history spanning various periods, each leaving a distinct mark on the architectural landscape:

Gothic Period (12th to 16th centuries): The Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris (begun in 1163) stands as an iconic example of French Gothic architecture, featuring pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and stunning stained glass windows. Other notable Gothic structures include Chartres Cathedral and the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.

Renaissance Period (15th to 17th centuries): The Château de Chambord (constructed in the early 16th century) epitomizes French Renaissance architecture with its grandiose design and intricate details. The Louvre Palace, initially built as a fortress in the late 12th century and transformed during the Renaissance, showcases a fusion of styles.

Baroque and Rococo Periods (17th to 18th centuries): The Palace of Versailles (constructed in the 17th century) under Louis XIV reflects the opulence of French Baroque architecture, featuring grand gardens, lavish interiors, and expansive halls. The Petit Trianon within the Versailles estate exemplifies Rococo elegance.

Haussmannian Architecture (19th century): Paris underwent extensive urban redevelopment under Baron Haussmann in the mid-19th century, leading to the creation of wide boulevards, grand squares, and uniform building facades, shaping the city's current architectural character.

These projects showcase the evolution of French architecture, highlighting significant styles and influential constructions that have shaped architectural history not only in France but also internationally.

French Architecture Building Materials

Throughout the various eras of French architecture, a wide array of materials were used to construct iconic buildings:

Stone: Stone was a primary material in French architecture, especially in medieval and Gothic structures. Limestone, sandstone, and marble were extensively used for walls, columns, and intricate carvings due to their durability and aesthetic appeal.

Timber and Wood: Wood was utilized in various periods, particularly in constructing roofs, frames, and interior elements. Traditional timber-framed houses in rural areas and wooden roof structures were common in medieval architecture.

Brick: Bricks were employed in constructing walls, vaults, and floors, becoming more prevalent during the Renaissance and later periods. They were often used alongside stone in structural components.

Plaster: Plaster was applied as a finishing material for interior walls and ceilings. Elaborate plasterwork and decorative moldings adorned many Baroque and Rococo buildings.

Metal: Iron and other metals were used for structural support, decorative elements like railings, gates, and sometimes roofing materials, particularly in more modern architectural styles.

Glass: The development of stained glass windows was a significant feature of French Gothic architecture, utilizing colored glass for intricate designs and narratives in cathedrals and churches.

The diverse use of these materials across different periods reflects the evolution of construction techniques and architectural styles in France, contributing to the country's rich architectural heritage.

Conclusion